Video: David Silver’s Youtube lecture series

Book: Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction

Supervised vs Evaluative Learning

For many problems of interest, the paradigm of supervised learning doesn’t give us the flexibility we need. The main difference between supervised learning and reinforcement learning is whether the feedback received is evaluative or instructive. Instructive feedback tells you how to achieve your goal, while evaluative feedback tells you how well you achieved your goal. Supervised learning solves problems based on instructive feedback, and reinforcement learning solves them based on evaluative feedback. Image classification is an example of a supervised problem with instructive feedback; when the algorithm attempts to classify a certain piece of data it is told what the true class is. Evaluative feedback, on the other hand, merely tells you how well you did at achieving your goal. If you were training a classifier using evaluative feedback, your classifier might say “I think this is a dog, and in return it would receive 50 points. Without any more context, we really don’t know what 50 points means. We would need to make other classifications and explore to find out whether our 50 points means that we were accurate or not. Maybe 10,000 is a more respectable score, but we just don’t know until we attempt to classify some other data points.

In many problems of interest, the idea of evaluative feedback is much more intuitive and accessible. For example, imagine a system that controls the temperature in a data center. Instructive feedback doesn’t seem to make much sense here, how do you tell your algorithm what the correct setting of each component is at any given time step? Evaluative feedback makes much more sense. You could easily feed back data such as how much electricity was used for a certain time period, or what was the average temperature, or even how many machines overheated. This is actually how Google tackles the problem, with reinforcement learning. So let’s jump straight into it.

Markov Decision Processes

A state \(s\) is said to be Markov if the future from that state is conditionally independent of the past given that we know \(s\). This means that \(s\) describes all the past states up until that current state. If that doesn’t make much sense, it is much easier to see it by example. Consider a ball flying through the air. If its state is its position and velocity, that is sufficient to describe where it has been and where it will go (given a physics model and that there are no outside influences). Therefore, the state has the Markov property. However, if we only knew the position of the ball but not its velocity, its state is no longer Markov. The current state doesn’t summarize all past states, we need information from the previous time step to start building a proper model of the ball.

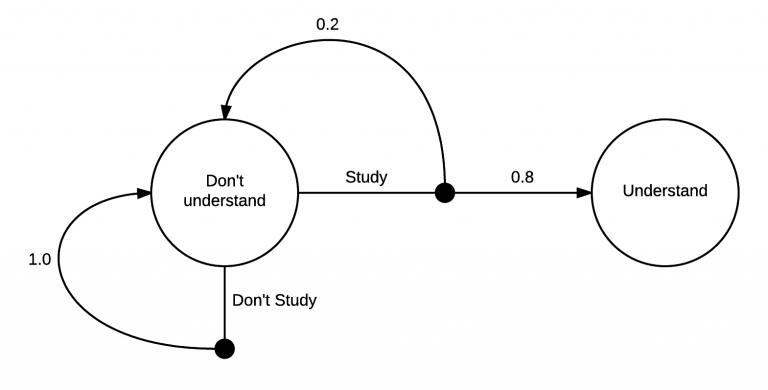

Reinforcement Learning is most often modeled as a Markov Decision Process, or MDP. An MDP is a directed graph which has states for its nodes and edges which describe transitions between Markov states. Here is a simple example:

|

This MDP shows the process of learning about MDPs. At first you are in the state Don’t understand. From there, you have two possible actions, Study or Don’t Study. If you choose to not study, there is a 100% chance that you will end up back in the Don’t understand state. However, if you study, there is a 20% chance you’ll end up back where you started, but an 80% chance of ending up in the Understand state.

Really, I’m sure there’s a much higher than 80% chance of transitioning to the understand state, at the core of it, MDPs are really very simple. From a state there are a set of actions you can take. After you take an action there is some distribution over what states you can transition into. As in the case of the Don’t Study action, the transition could very well be deterministic too.

The goal in reinforcement learning is to learn how to act to spend more time in more valuable states. To have a valuable state we need more information in our MDP.

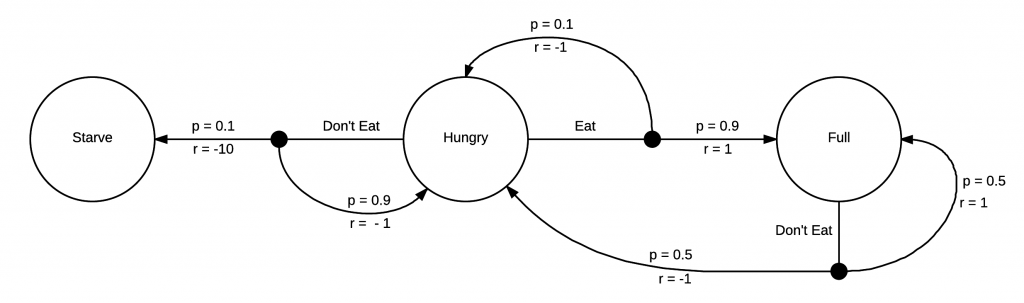

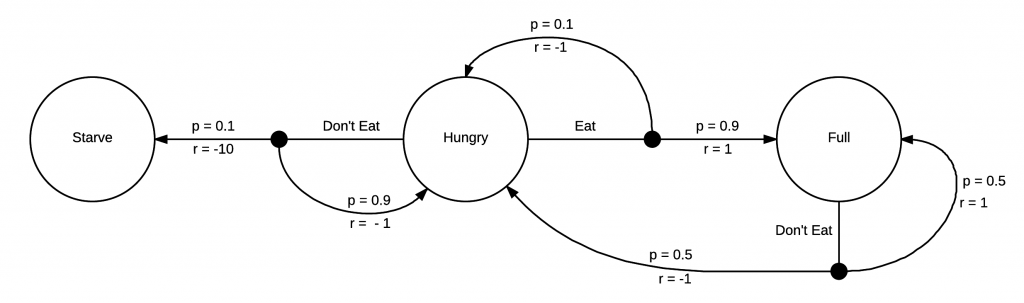

|

This MDP has the addition of rewards. Each time you make a transition into a state, you receive a reward. In this example, you get negative rewards for ending up being hungry, and a large negative reward for starving. If you become full, however, you receive a positive reward. Now that our MDP is fully formed, we’re able to start thinking about how to make actions to receive the greatest possible reward!

Since this MDP is very simple, it is easy to see that the way to stay in areas of higher reward is to eat whenever we’re hungry. We don’t have much choice of how to act when we’re full in this model, but we will inevitably end up hungry again and could immediately choose to eat. Problems that are of interest to solve with reinforcement learning have much larger, much more complex MDPs, and often we don’t know them before hand but need to learn them from exploration.

Formalizing the Reinforcement Learning Problem

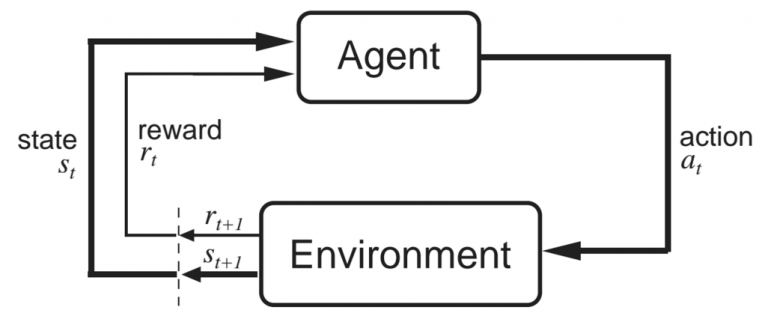

Now that we have many of the building blocks we need we should look at the terminology used in RL. The most important components are the agent and the environment. An agent exists in some environment which it has indirect control over. By looking back at our MDPs, the agent can choose which action to take in a given state, which has a significant effect on the states it sees. However, the agent does not control the dynamics of the environment completely. The environment, upon receiving these actions, returns the new state and the reward.

|

This image explains the agent and environment interactions very well. At some time step \(t\), the agent is in state \(s_t\) and takes an action \(a_t\). The environment then responds with a new state \(s_{t+1}\) and a reward \(r_{t+1}\). The reason that the reward is at \(t+1\) is because it is returned with the environment with the state at \(t+1\), so it makes sense to keep them together (as in the image).

We now have a framework for the reinforcement learning problem, and are ready to start looking at how to go about maximizing our reward. We will learn about state value functions and action value functions, as well as the Bellman equations which make the foundation for the algorithms for solving reinforcement learning problems.

Reward and Return

RL agents learn to maximize cumulative future reward. The word used to describe cumulative future reward is return and is often denoted with \(R\). We also use a subscript \(t\) to give the return from a certain time step. In mathematical notation, it looks like this:

\[R_t = r_{t+1} + r_{t+2} + r_{t+3} + r_{t+4} + \dots = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} r_{t+k+1}\]If we let this series go on to infinity, then we might end up with infinite return, which really doesn’t make a lot of sense for our definition of the problem. Therefore, this equation only makes sense if we expect the series of rewards to end. Tasks that always terminate are called episodic. Card games are good examples of episodic problems. The episode starts by dealing cards to everyone, and inevitably comes to an end depending on the rules of the particular game. Then, another episode is started with the next round by dealing the cards again.

More common than using future cumulative reward as return is using future cumulative discounted reward:

\[R_t = r_{t+1} + \gamma r_{t+2} + \gamma^2 r_{t+3} + \gamma^3 r_{t+4} + \dots = \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+1}\]where 0 < \(\gamma\) < 1. The two benefits of defining return this way is that the return is well defined for infinite series, and that it gives a greater weight to sooner rewards, meaning that we care more about imminent rewards and less about rewards we will receive further in the future. The smaller the value we select for \(\gamma\) the more true this is. This can be seen in the special cases where we let \(\gamma\) equal 0 or 1. If \(\gamma\) is 1, we arrive back at our first equation where we care about all rewards equally, not matter how far into the future they are. On the other hand, when \(\gamma\) is 0 we care only about the immediate reward, and do not care about any reward after that. This would lead our algorithm to be extremely short-sighted. It would learn to take the action that is best for that moment, but won’t take into account the effects that action will have on its future.

Policies

A policy, written \(\pi (s, a)\), describes a way of acting. It is a function that takes in a state and an action and returns the probability of taking that action in that state. Therefore, for a given state, it must be true that \(\sum_a \pi (s, a) = 1\). In the example below, when we are Hungry we can choose between two actions, Eat or Don’t Eat.

|

Our policy should describe how to act in each state, so an equiprobable random policy would look something like \(\pi (hungry, E) = 0.5\), \(\pi(hungry, \overline{E}) = 0.5\), \(\pi(full, \overline{E}) = 1.0\) where \(E\) is the action Eat, and \(\overline{E}\) is the action Don’t Eat. This means that if you are in the state Hungry, you will choose the action Eat and Don’t Eat with equal probability.

Our goal in reinforcement learning is to learn an optimal policy, \(\pi^*\). An optimal policy is a policy which tells us how to act to maximize return in every state. Since this is such a simple example, it is easy to see that the optimal policy in this case is to always eat when hungry, \(\pi^*(hungry, E) = 1.0\). In this instance, as is the case for many MDPs, the optimal policy is deterministic. There is one optimal action to take in each state. Sometimes this is written as \(\pi^*(s) = a\), which is a mapping from states to optimal actions in those states.

Value Functions

To learn the optimal policy, we make use of value functions. There are two types of value functions that are used in reinforcement learning: the state value function, denoted \(V(s)\), and the action value function, denoted \(Q(s, a)\).

The state value function describes the value of a state when following a policy. It is the expected return when starting from state s acting according to our policy \(\pi\):

\[V^{\pi}(s) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \big[R_t | s_t = s \big]\]It is important to note that even for the same environment the value function changes depending on the policy. This is because the value of the state changes depending on how you act, since the way that you act in that particular state affects how much reward you expect to see. Also note the importance of the expectation. (As a refresher, an expectation is much like a mean; it is literally what return you expect to see.) The reason we use an expectation is that there is some randomness in what happens after you arrive at a state. You may have a stochastic policy, which means we need to combine the results of all the different actions that we take. Also, the transition function can be stochastic, meaning that we may not end up in any state with 100% probability. Remember in the example above: when you select an action, the environment returns the next state. There may be multiple states it could return, even given one action. We will see more of this as we look at the Bellman equations. The expectation takes all of this randomness into account.

The other value function we will use is the action value function. The action value function tells us the value of taking an action in some state when following a certain policy. It is the expected return given the state and action under \(\pi\):

\[Q^{\pi}(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \big[ R_t | s_t = s, a_t = a \big]\]The same notes for the state value function apply to the action value function. The expectation takes into account the randomness in future actions according to the policy, as well as the randomness of the returned state from the environment.

The Bellman Equations

Richard Bellman was an American applied mathematician who derived the following equations which allow us to start solving these MDPs. The Bellman equations are ubiquitous in RL and are necessary to understand how RL algorithms work. But before we get into the Bellman equations, we need a little more useful notation. We will define \(\mathcal{P}\) and \(\mathcal{R}\) as follows:

\[\mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a} = Pr(s_{t+1} = s' | s_t = s, a_t = a)\]\(\mathcal{P}\) is the transition probability. If we start at state \(s\) and take action \(a\) we end up in state \(s'\) with probability \(\mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a}\).

\[\mathcal{R}_{s s'}^{a} = \mathbb{E}[ r_{t+1} | s_t = s, s_{t+1} = s', a_t = a ]\]\(\mathcal{R}_{s s'}^{a}\) is another way of writing the expected (or mean) reward that we receive when starting in state \(s\), taking action \(a\), and moving into state \(s'\).

Finally, with these in hand, we are ready to derive the Bellman equations. We will consider the Bellman equation for the state value function. Using the definition for return, we could rewrite equation as follows:

\[V^{\pi}(s) =\mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[r_{t+1} + \gamma r_{t+2} + \gamma^2 r_{t+3} + \dots | s_t = s \Big] = \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+1} | s_t = s \Big]\]If we pull out the first reward from the sum, we can rewrite it like so:

\[V^{\pi}(s) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[r_{t+1} + \gamma \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+2} | s_t = s \Big]\]The expectation here describes what we expect the return to be if we continue from state \(s\) following policy \(\pi\). The expectation can be written explicitly by summing over all possible actions and all possible returned states. The following equations can help us make the step.

\[\mathbb{E}_{\pi} [r_{t+1} | s_t = s] = \sum_{a} \pi(s, a) \sum_{s'} \mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a} \mathcal{R}_{s s'}^{a}\] \[\mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ \gamma \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+2} | s_t = s \Big] = \sum_{a} \pi(s, a) \sum_{s'} \mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a} \gamma \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+2} | s_{t+1} = s' \Big]\]By distributing the expectation between these two parts, we can then manipulate our equation into the form:

\[V^{\pi}(s) = \sum_{a} \pi (s, a) \sum_{s'} \mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a} \Bigg[ \mathcal{R}_{s s'}^{a} +\gamma \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+2} | s_{t+1} = s' \Big] \Bigg]\]Now, note that equation is in the same form as the end of this equation. We can therefore substitute it in, giving us

\[V^{\pi}(s) = \sum_{a} \pi (s, a) \sum_{s'} \mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a} \Big[ \mathcal{R}_{s s'}^{a} + \gamma V^{\pi}(s') \Big]\]The Bellman equation for the action value function can be derived in a similar way.

\[Q^{\pi}(s, a) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ r_{t+1} + \gamma r_{t+2} + \gamma^2 r_{t+3} + ... | s_t = s, a_t = a \Big] = \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ \sum_{k = 0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t + k + 1} | s_t = s, a_t = a \Big]\] \[Q^{\pi}(s,a) = \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ r_{t+1} + \gamma \sum_{k=0}^{\infty}\gamma^k r_{t+k+2} | s_t = s, a_t = a \Big]\] \[Q^{\pi}(s,a) = \sum_{s'} \mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a} \Bigg[ \mathcal{R}_{s s'}^{a} + \gamma \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+2} | s_{t+1} = s' \Big] \Bigg]\] \[Q^{\pi}(s,a) = \sum_{s'} \mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a} \Bigg[ \mathcal{R}_{s s'}^{a} + \gamma \sum_{a'} \mathbb{E}_{\pi} \Big[ \sum_{k=0}^{\infty} \gamma^k r_{t+k+2} | s_{t+1} = s', a_{t+1} = a' \Big] \Bigg]\] \[Q^{\pi}(s,a) = \sum_{s'} \mathcal{P}_{s s'}^{a} \Big[ \mathcal{R}_{s s'}^{a} + \gamma \sum_{a'} \pi (s', a') Q^{\pi}(s', a') \Big]\]The importance of the Bellman equations is that they let us express values of states as values of other states. This means that if we know the value of \(s_{t+1}\), we can very easily calculate the value of \(s_t\). This opens a lot of doors for iterative approaches for calculating the value for each state, since if we know the value of the next state, we can know the value of the current state.